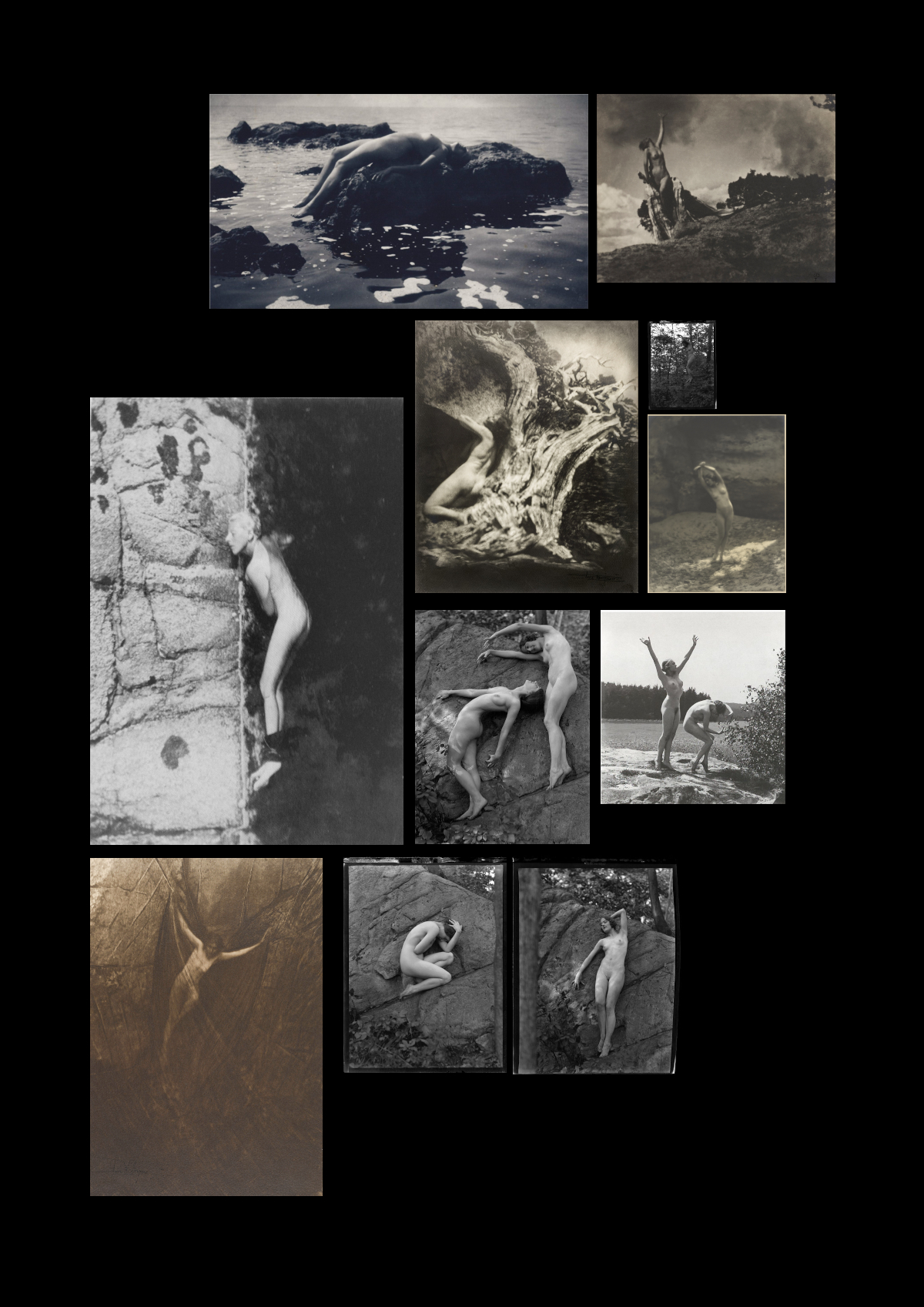

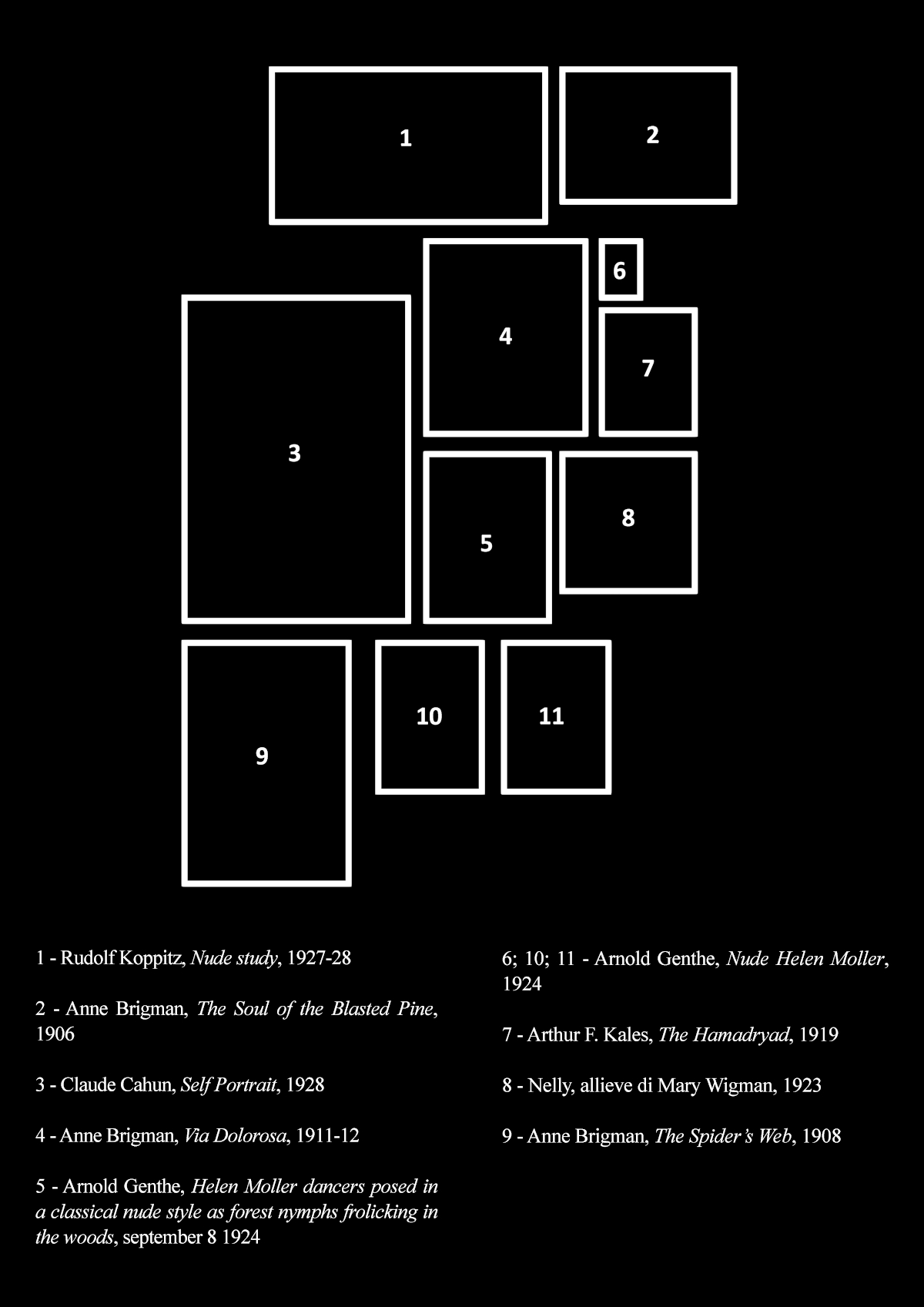

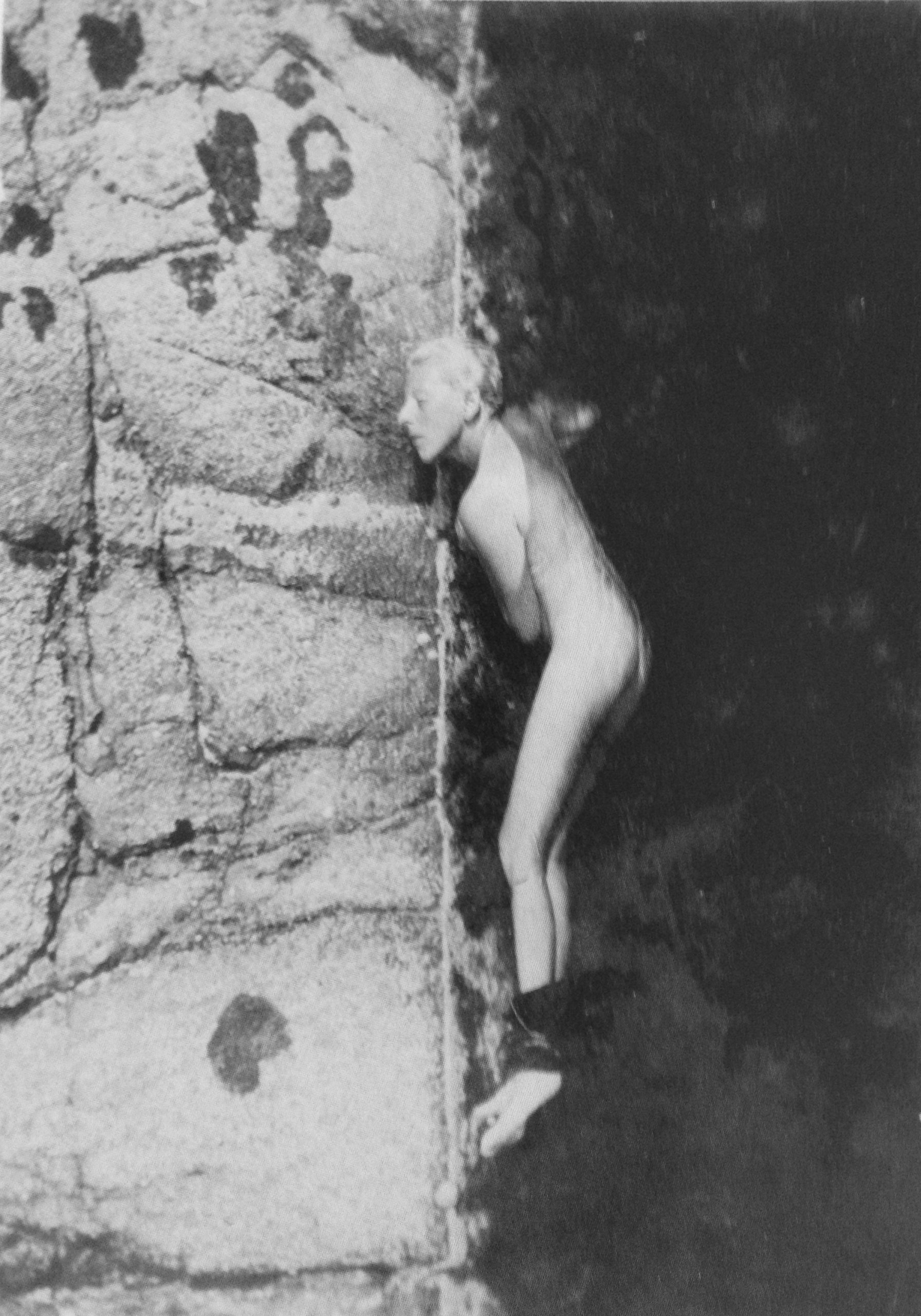

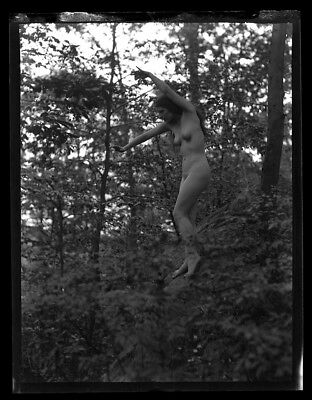

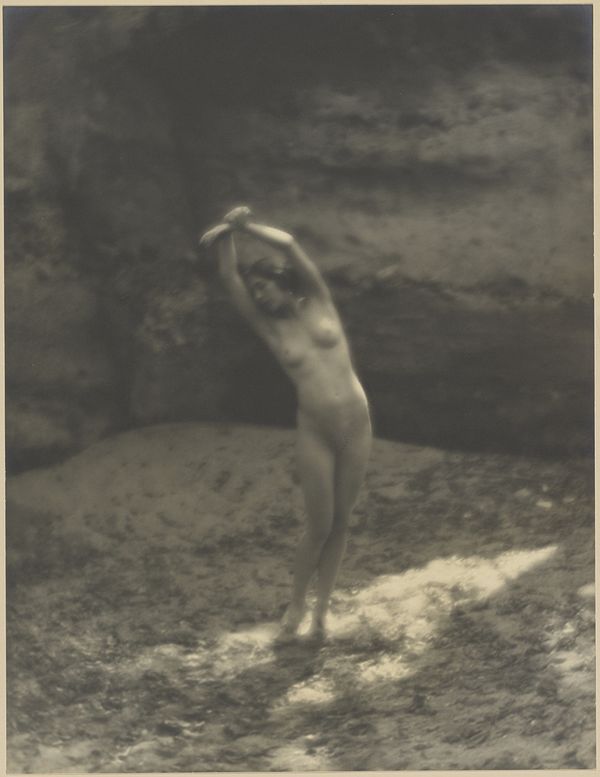

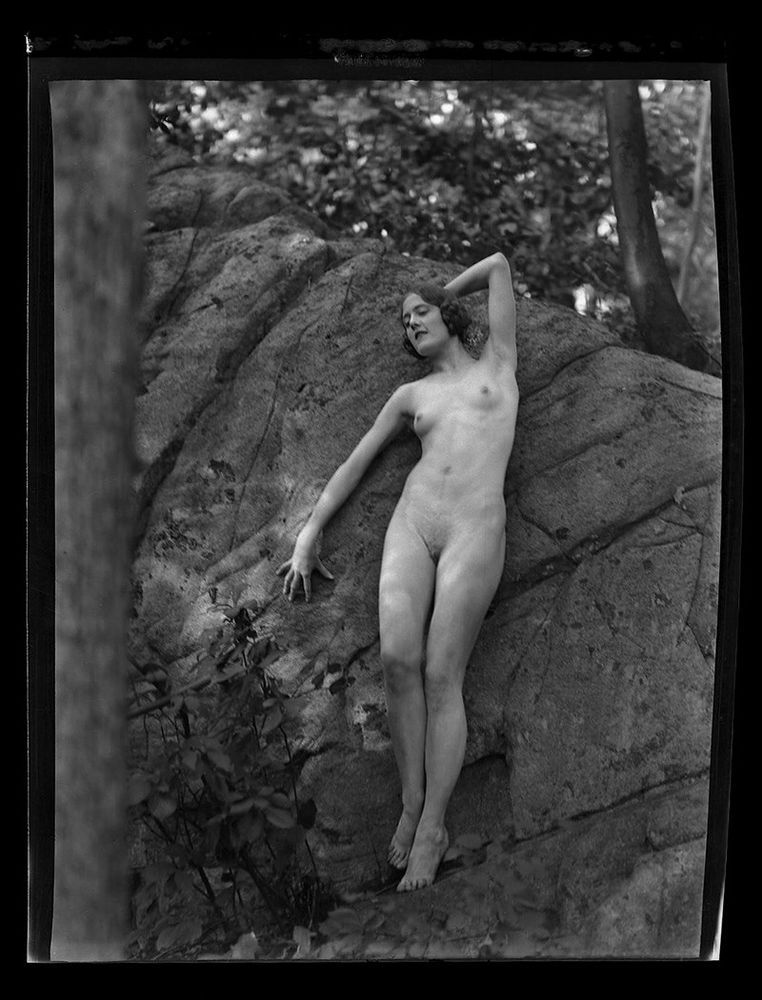

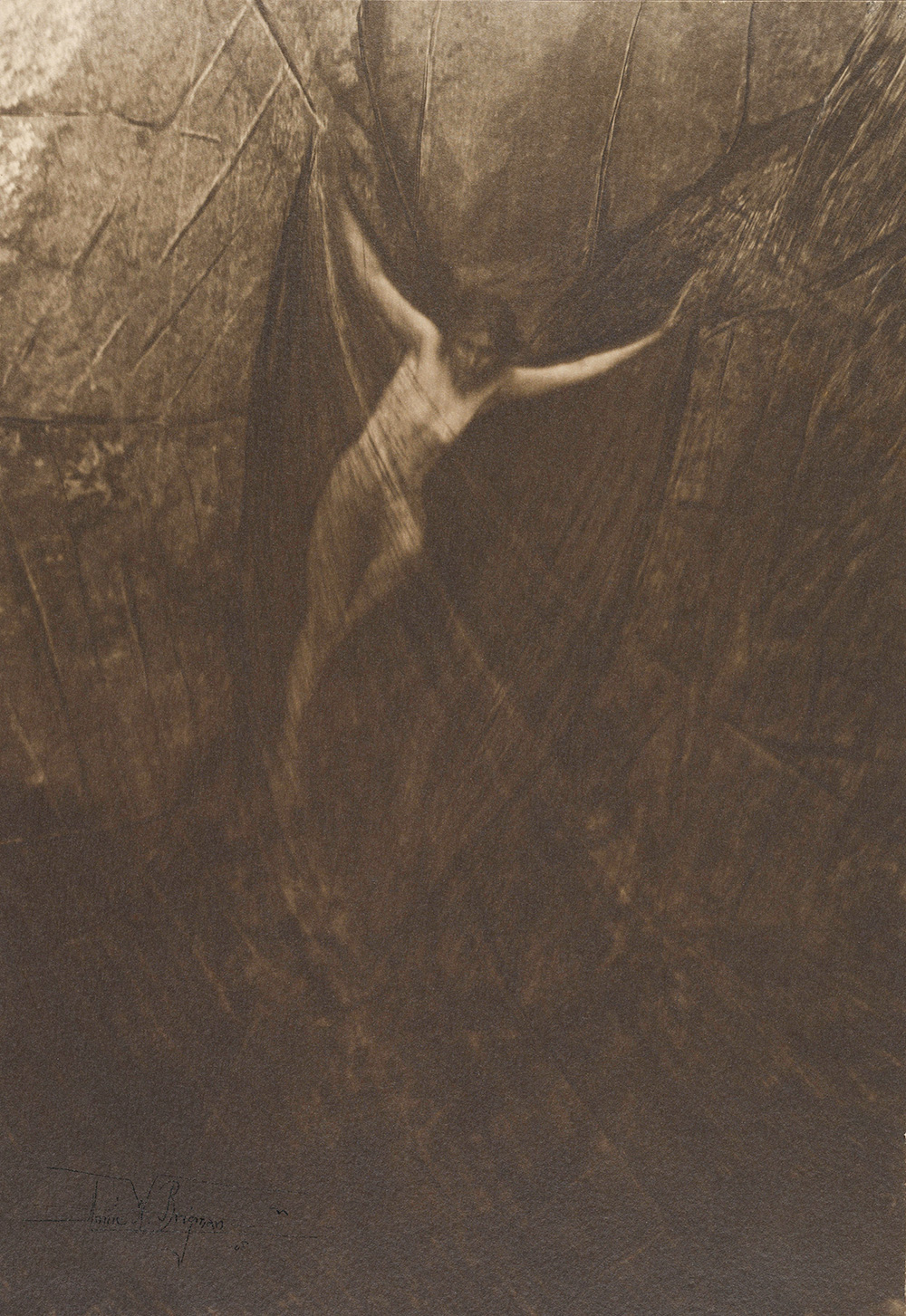

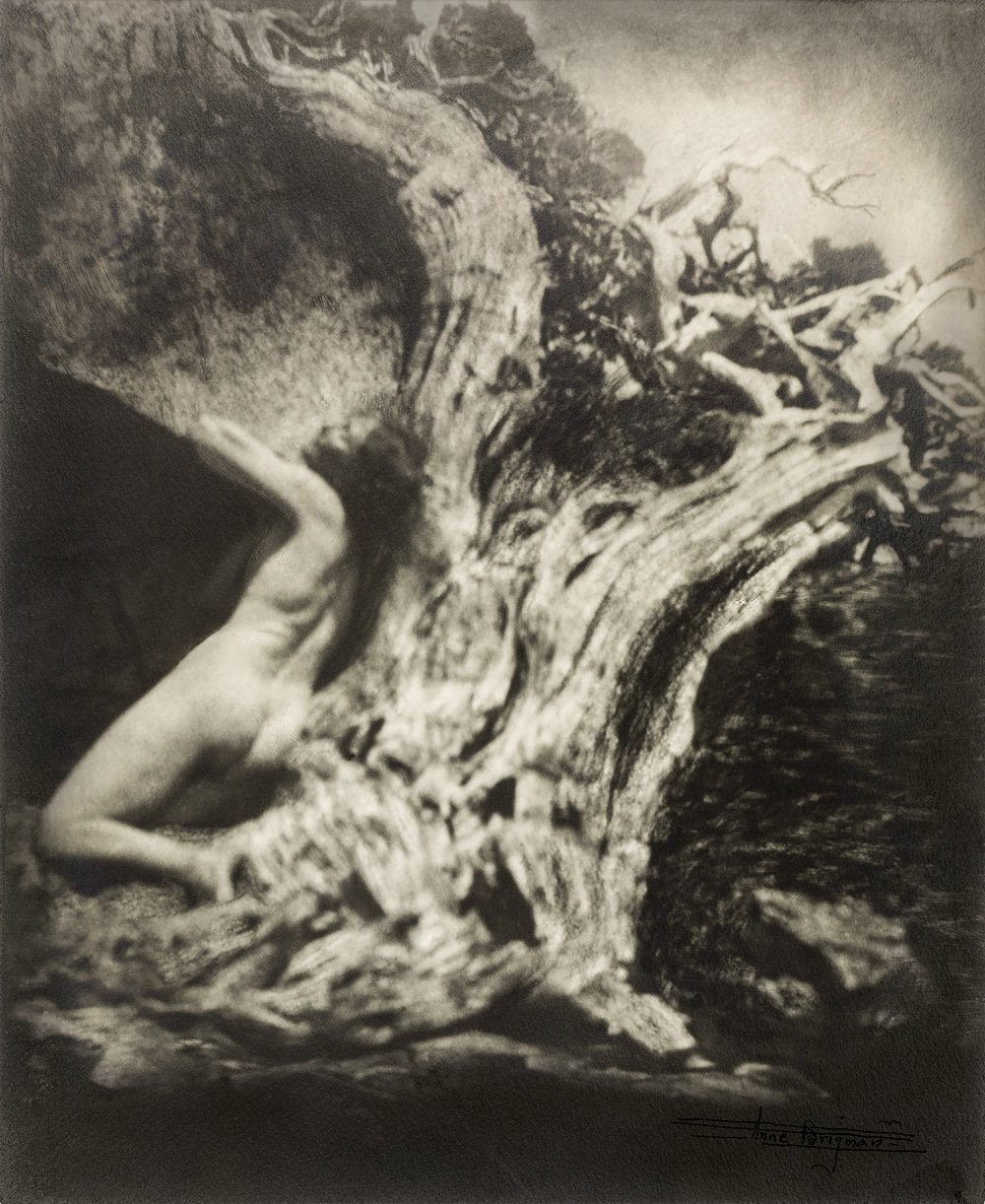

«Nuove dimensioni si rivelarono nella visualizzazione delle forme umane come parte dei ritmi di alberi e rocce…». È il 1936, e a scrivere è Anne Brigman (Honolulu 1869 – El Monte 1950), fotografa californiana di origine hawaiana ed esponente del movimento foto-secessionista americano. Avvicinatasi alla fotografia nei primissimi anni del secolo, entra presto in contatto con il gruppo dei foto-secessionisti newyorkesi e stabilisce una corrispondenza diretta con Alfred Stieglitz. In questa fase di sperimentazione, e sul levare del decennio, comincia a esplorare l’identità femminile ritraendo, o autoritraendo, il corpo nudo immerso nella natura incontaminata della Bay Area californiana. I testi di Anne Brigman, così come le poesie scritte e raccolte in Songs of a Pagan (1949), restituiscono con grande esattezza la qualità emozionale e atmosferica di quei momenti ma insieme ci rendono chiaro come non potremo mai essere lì senza essere davvero lì, con i nostri corpi.

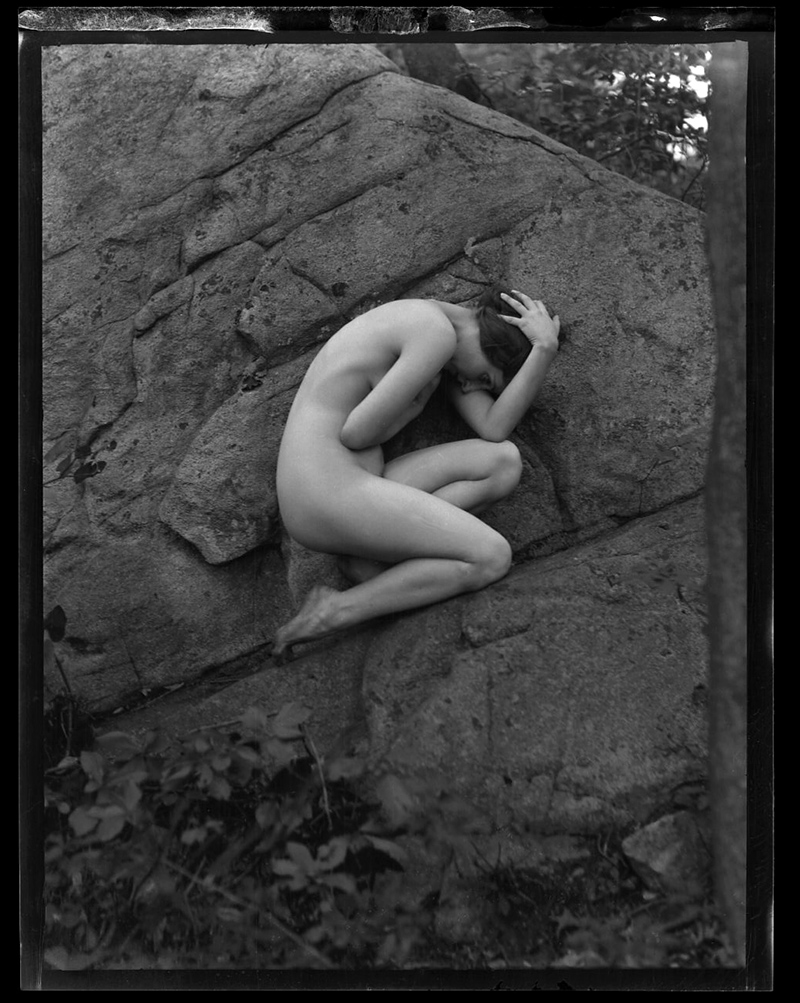

L’irriproducibilità della presenza umana che fa esperienza dell’ambiente circostante, dove ritmi, connessioni paniche e riti pagani sono consumati in un determinato e irripetibile stato di amplificazione percettiva, come nell’esperienza di Brigman, evoca la danza perché determina lo stato atmosferico di un ambiente attraverso un corpo. Senza quel corpo che lo agita o interroga, l’ambiente cambia di segno, e l’esperienza che se ne fa non è già più la stessa. I corpi nudi delle fotografie di Brigman, così come il corpo di Claude Cahun, incastrato tra l’acqua e la roccia, esplorano forme e consistenze naturali di cui assecondano ritmi, linee e volontà. Vi si abbandonano in ascolto, o ne traggono forza e coscienza danzandovi assieme.

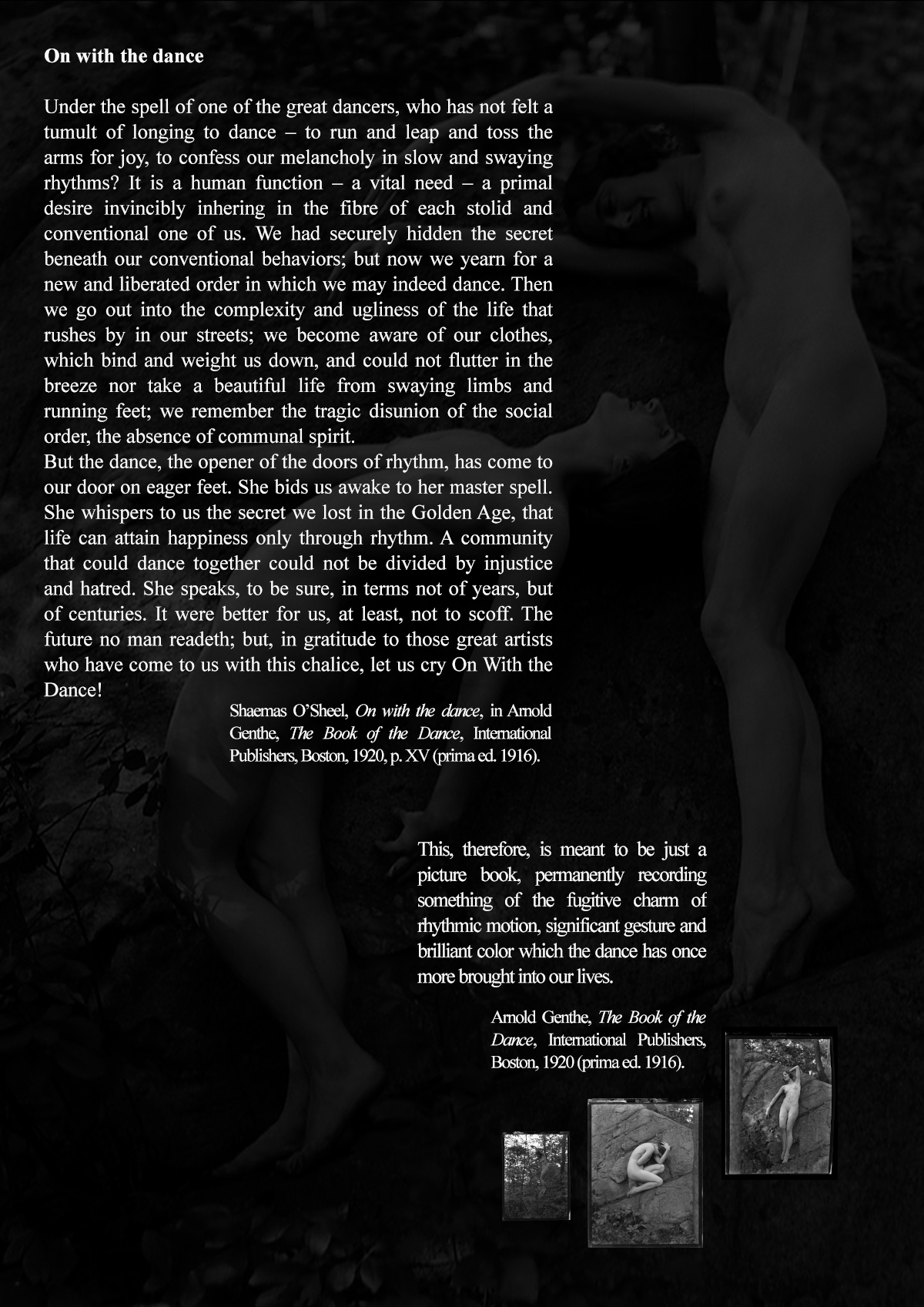

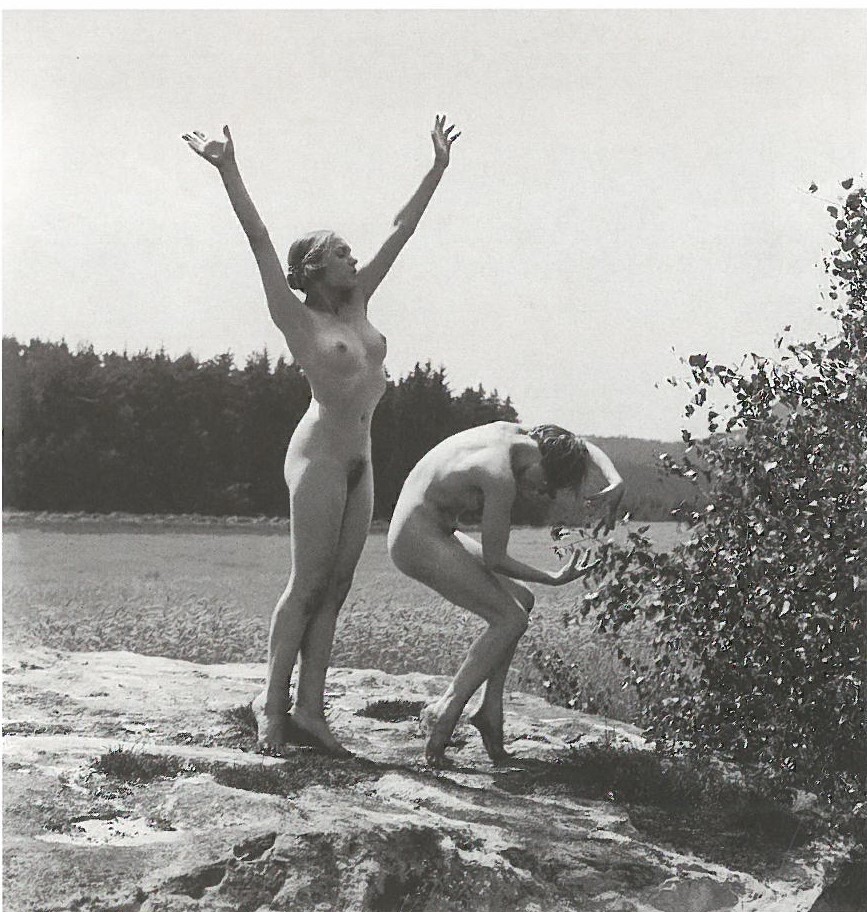

The Book of the Dance viene pubblicato nel 1916 da Arnold Genthe (Berlino 1869 – New York 1942), pochi anni dopo il suo trasferimento da San Francisco a New York, nel 1911. In apertura, nell’edizione del 1920, compare On with the dance, testo di Shaemas O’Sheel che presenta la raccolta motivando le scelte compiute dall’autore e ragionando, con grande trasporto narrativo, su alcune questioni interessanti per il rapporto tra nudo e ambiente, e, per ciò che ci interessa, tra nudo e fotografia. L’incantesimo della danza, che ci spinge a desiderare letteralmente di poter danzare, afferma O’Sheel, è una funzione umana e una esigenza ma soprattutto una prova di consapevolezza: dei vestiti che pesantemente indossiamo, dell’ordine sociale sotto cui talvolta soccombiamo. La danza, arrivata alle nostre porte con i piedi impazienti, ci costringe a fare i conti con la libertà.

Le fotografie di Arnold Genthe che, nel 1924, ritraggono la danzatrice e coreografa Helen Moller danzare su una parete rocciosa, riproducono e tramandano a noi questa gioiosa libertà, dei gesti e degli sguardi. L’incantesimo di cui anche a distanza di tempo e di spazio riusciamo a essere vittime, la gratitudine di un corpo assolto ed emancipato dai propri gesti. Così Rudolf Koppitz, Arthur F. Kales e Nelly, intersecano, in ambienti geografici e culturali più o meno distanti e dissimili, la stessa volontà pacificatrice. Il braccio è un ramo, le gambe un tronco, le mani descrivono una chioma. In piedi o disteso nell’ambiente naturale, il corpo nudo prende e accoglie, restituisce la sua azione come una parte ricevuta in dono e riabitata, ora, da nuovi significati. [Francesca Pietrisanti]

One day during the gathering of the thunder storm when the air was hot and still and a strange yellow light was over everything, something happened almost too deep for me to be able to relate. New dimensions revealed themselves in the visualization of the human form as a part of tree and rock rhythms and I turned full force to the medium at hand [photography] and the beloved thing gave to me a power and abandon that I could not have had otherwise. [Anne Brigman, Awareness, «Design for Arts in Education», n. 38, June 1936, p. 18, riportato in Susan Eherens (a cura di), A Poetic Vision. The Photographs of Anne Brigman, Santa Barbara Museum of Art, Santa Barbara 1995, p. 23]

* * *

I slowly found my power with the camera among

the junipers and the tamrack pines of the high,

storm-swept altitudes.

Compact, squat giants are these trees, shaped by the

winds of the centuries like wings and flames and torso-

like forms… unbelievably beautiful in their rhythms.

Here stored consciousness began its work…

not only with the splendor of the strange trees, but a

sense of visualization developed in amazing ways in

which the human figure suggested itself as part of

their motive…

[Anne Brigman, hand-typed manuscript, 1939, The Oackland Museum Archives, I, riportato in Susan Eherens, (a cura di), A Poetic Vision. The Photographs of Anne Brigman, Santa Barbara Museum of Art, Santa Barbara 1995, p. XII]

On with the dance

On with the dance

Under the spell of one of the great dancers, who has not felt a tumult of longing to dance – to run and leap and toss the arms for joy, to confess our melancholy in slow and swaying rhythms? It is a human function – a vital need – a primal desire invincibly inhering in the fibre of each stolid and conventional one of us. We had securely hidden the secret beneath our conventional behaviors; but now we yearn for a new and liberated order in which we may indeed dance. Then we go out into the complexity and ugliness of the life that rushes by in our streets; we become aware of our clothes, which bind and weight us down, and could not flutter in the breeze nor take a beautiful life from swaying limbs and running feet; we remember the tragic disunion of the social order, the absence of communal spirit.

But the dance, the opener of the doors of rhythm, has come to our door on eager feet. She bids us awake to her master spell. She whispers to us the secret we lost in the Golden Age, that life can attain happiness only through rhythm. A community that could dance together could not be divided by injustice and hatred. She speaks, to be sure, in terms not of years, but of centuries. It were better for us, at least, not to scoff. The future no man readeth; but, in gratitude to those great artists who have come to us with this chalice, let us cry On With the Dance! [Shaemas O Sheel, On with the dance, in Arnold Genthe, The Book of the Dance, International Publishers, Boston 1920 (prima ed. 1916), p. XV]

* * *

This, therefore, is meant to be just a picture book, permanently recording something of the fugitive charm of rhythmic motion, significant gesture and brilliant color which the dance has once more brought into our lives. [Arnold Genthe, The Book of the Dance, International Publishers, Boston 1920 (prima ed. 1916)]